By Christina Milliman

Many people local to the Mohawk, Leatherstocking, and Catskill regions know that historically this area was known for the cultivation of hops. But when? Do we know when those seemingly wild hops that now grow on our properties, in our fields, and on our mailbox posts were planted? When were Otsego and Madison Counties known for producing the “King Crop”?

In the collections of the Fenimore Art Museum and The Farmers’ Museum are books, diaries, letters, hop rhymes, tools of the trade, and photographs that tell this story. By 1880, Otsego County hop yards grew and sold the most hops of any place in the United States. Hop yards owned by Taugers, Clarks, and Buschs in Otsego County produced a majority of the hops – 80% of the entire U.S. crop. Have you ever seen a hop cone? Picked one? Held one in your hand?

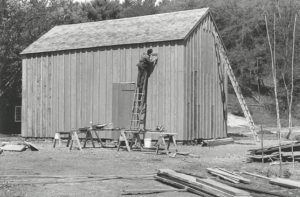

Several varieties of hops were grown in this region, including fuggles and English cluster. Root stock were placed in the ground in hills. Once they emerged they were trained to climb tall poles, generally 12 to 16 feet tall, as seen in the background of the photo here. Near the end of August and into early September in the Northeast, the cones would be ready for picking. In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, this work was mostly done by migrant workers. Entire families came; entire families picked. Each cone was painstakingly picked by hand from the vine, and placed into a large hop box consisting of four quadrants.

Once a box was filled, pickers would receive a ticket with their name and number of boxes filled. This ticket could be traded in for goods or money. The cones were then dried in a hop kiln, a barn-like structure found on many farms in the area and certainly in the hop yards. Once the hop cones were dried, they were often baled and dried further, then shipped to market. Remnants of the kilns still exist today, and can be found on country roads and on old farm properties. The Pope Hop House at The Farmers’ Museum can still be explored today.

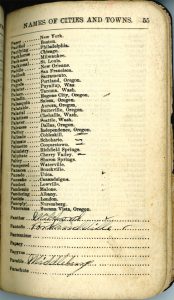

One interesting hop industry item in the Museum’s Library is the “Telegraphic Cipher” book dated 1890. This book lists codes used by buyers and sellers to keep the content of their conversations hidden because telegrams, while quick, were not private. The book lists ciphers for such things as dates, varieties of hops for sale, condition of the crop, origin and more. For example, Palmetto in the book means “Cooperstown” and Famously means “Otsego County Hops.”

How is this history kept alive today? Many hop yards have been started in the area in recent years. Among these are Hager Hops in Cooperstown and Muddy River Hops in Unadilla. Although these hop yards are not open to the public, you can often catch a glimpse of the preparation necessary – hop vines growing up strings fastened to tall poles – and can just imagine the painstaking work it takes even today to help each small cone and vine prosper.

On view in the Museum Library is an exhibition created by students of the Cooperstown Graduate Program of SUNY Oneonta discussing the history of the hop industry in Otsego County in the late 1800s and early 1900s. And this past August, The Farmers’ Museum held a first-time event, Hopsego, celebrating the history of hops and the resurgence of hop growing in our region today. Look for this second annual family-friendly, hop-centric event in August 2018

For more information about the history of hops in Otsego County, see photographs online in the Plowline: Images of Rural New York collection (plowline.farmersmuseum.org) at The Farmers’ Museum, peruse the Smith & Telfer photographic collection, or seek out the many books available on the subject by visiting the Museum’s Library.

Christina Milliman is Curator of Photography, Fenimore Art Museum and The Farmers’ Museum