by Alexis Green

New York will never produce as much shale gas as Pennsylvania.

That’s the consensus of four retired experts: a geologist, an engineer, an oil executive and an oil investor. They spoke on January 16 at the New York Society for Ethical Culture in Manhattan. Their topic: “New York Shale Gas Potential: How Does It Compare to Pennsylvania?” (See video of this talk below.)

The four men – geologist and Franklin resident Brian Brock; James (Chip) Northrup; Thomas G. (Jerry) Acton; and Lou Allstadt – demolished the notion that the Marcellus or Utica shales beneath New York State can produce the large volume of natural gas which the DEC and fossil fuel companies claim exists. Dr. Anthony Ingraffea, a Cornell Professor of Engineering, moderated the evening, as he did last October for the panel in Ithaca.

Many of us who live in the Southern Tier know the myths purveyed by fossil fuel companies eager to bring hydraulic fracturing to our neighborhoods. These myths promise local job creation and fat royalties in exchange for drilling rights and, of course, no spillage or contamination.

But the biggest myth of all? An abundance of shale gas beneath New York’s rocky surface.

The story begins with geology, Brock told the audience, around 150 people assembled in the Society’s domed, wood-paneled auditorium.

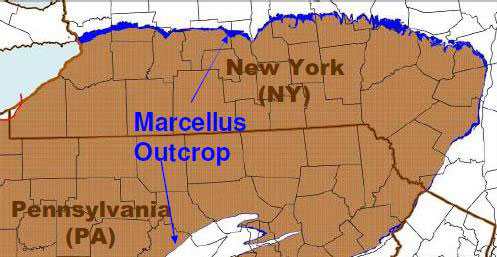

A productive shale well, he explained, needs a perfect storm of organic content, thermal maturity, thickness, and depth. Most of New York’s shale is either “barren and overcooked” (the Catskills) or “thin and shallow” (much of the Southern Tier). Either way, Brock said, “shale drilling in New York will never reap the bonanza it has in Pennsylvania.”

Acton, a retired IBM and Lockheed Martin systems engineer, analyzed publicly available data from 1,795 productive Pennsylvania wells in 6 counties along the Northern Tier and 1,023 wells in southwest PA, all drilled from 2009 to 2013.

Supporting the conventional wisdom of the industry, Acton’s maps, graphs and distilled data demonstrated that the most productive Pennsylvania wells occur where the Marcellus shale is thickest and deepest, largely at the intersection of Wyoming, Susquehanna and Bradford counties (the so-called “sweet spot”). To the north and west, where the shale formation becomes thinner and shallower – similar to New York’s – productivity drops off dramatically.

In New York, shale deposits with the most potential exist only in a few spots along the Pennsylvania border, and those sites don’t promise enough shale gas to make drilling economically viable at today’s prices.

Why, then, does the fossil fuel industry seem determined to hydrofrack in New York, if the geology and the economics are not on the industry’s side?

Once upon at time, hyping New York’s potential productivity drew investor capital and upped the value of a company’s shares. Lately, according to Allstadt, a retired executive of Mobil Oil Corporation, many oil and gas companies, deterred by the prospect of expensive drilling and low return, have pulled out of New York State. But other firms, he cautioned, may be eager to frack on the cheap despite the poor economics.

There are bigger threats, in Allstadt’s view: the lung-cancer-producing silica in the sand used during fracking; the methane emissions from pipeline leaks; radioactive material in the fluid that comes out along with the oil and gas; and the inadequate disposal of toxic fracking waste, which can drain into soil and water, endangering people upstate and down who eat local fish, meat and produce or drink water from the tap.

“Fracking has an impact hundreds of miles beyond the wells,” said Allstadt.

Take the chemical-laden fluid — euphemistically known as “brine” — that flows back to the surface after fracking. When not trucking it to Ohio for disposal, Pennsylvania uses it to de-ice roads during the winter. New York’s DEC says flowback water from hydrofracking is not being spread on the Empire State’s highways, but in 2013 the environmental group Riverkeeper (www.Riverkeeper.org) examined documents showing that for many years the DEC has given Beneficial Use Determinations, or BUDs, for brine from non-shale, vertical oil and gas wells.

State Senator Terry Gipson of Dutchess County has introduced Senate Bill 3333, which would keep flowback water from oil or natural gas wells off New York’s roads. But that would address only part of the threat. Allstadt notes that New York has no injection wells to handle fracking waste such as drill cuttings or used drilling mud. Northrup, a gangling Texan, formerly an executive at Atlantic Richfield, warned that in New York, “Most towns are not going to get fracked – they are going to get dumped on.”

The lesson from Pennsylvania, the panelists concluded, is that hydrofracking in New York would be a low-reward, high-risk project. There is still much to fight for, they told the audience. The story isn’t over yet.

Alexis Greene is an author and editor. She and her husband, Gordon Hough, work in NYC and live in a cabin outside of Walton.

See the series of videos of the Manhattan talk below (click on Playlist to see others in the series), or go directly to YouTube.