By Charlie Bremer

being swallowed whole

in the dark of night around her beautiful circular vessels

gives flight to all of us

Art is about transformation. We witness alchemy as the body and muscle of another person transmutes raw physical materials – clay, pigment, wood, metal, stirred with animated frequencies of light, sound, text, emotion, saturated with the elements: heat, air, water – and ultimately reshapes them with such grace and power as to transpose our sense of space and time. Through art we rise up, we take notice, we fall in love, we remember, we are moved to act, we join together, and we again recognize what and that we understand. We mark our place.

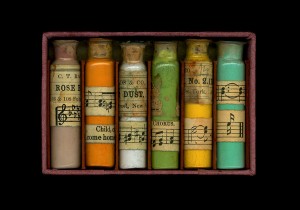

In the summer of 1961 at the edge of a roadside parking lot in western Wyoming, I encountered the most beautiful valley I had ever seen. I was eight years old, almost nine, and our family had traveled west camping for three long months over the summer. We were south of Yellowstone and just east of the Grand Teton Mountain Range with Jackson Hole Lake before us. On my lap was a blank sketch pad, in my hand a drawing pencil, and my mother had placed a box of American Crayon Company pastels at close reach. What followed, for the first time in my conscious life, I can only describe as being swallowed whole by the landscape before me. More than half a century later I can precisely recall the weightlessness of my body as I perceived myself floating foreword into an extra-dimensional space, the enormous valley floor between where I sat and the magnificent distant range of mountains beyond. The more I concentrated on visual artistic perceptions, the further and faster I levitated into the vast immense air. Shapes of trees, textures on the low hills, hues of green and umber in earthen vegetation grew completely sharp with light as I hovered optically over the earth. This out-of-body experience seemed like a trick the mountains themselves had conjured to combine with my youth and my intense concentration of artistic observation. Whatever it was, I loved it. The act of drawing had guided me to look closely, and the power of that moment through art was for me a luminous birth. Had I not been looking with the specific determination to draw and sketch, I believe I would never have experienced the Tetons Range so deeply that, to this day, I can see that valley clearly, in every detail.

From Jackson Hole, our family continued south and west that summer, crossing into Utah, traversing the plains of the Great Salt Lake, visiting ancient Anasazi cliff houses and passing through Four Corners, where we entered Navajo territory in present day New Mexico. One morning we broke camp outside of Santa Fe and drove to Pueblo San Ildefonso, arriving close to noon at the home of potter Maria Martinez. She was somewhere in her mid-seventies and reminded me of an ancient juniper, growing above tree line on a western plateau. I am fairly certain I never spoke a word to anyone that day. I just watched as this remarkable woman demonstrated her clay work, served us some lunch and tended a firing of pots which appeared as a big smoldering pile of dried animal dung and sticks nearby on the ground. She polished her simple plates and bowls with smooth stones and then painted each of them with a clay slip as smooth as cream. As a young boy I was completely in love with clay, and still am. What Maria did for me with this refined earth was pure magic: she gave it wings both literally and figuratively, with black on black creation. Her work space and art gave life to my seeing beauty in a hand-made object, and her wings, in every sense and meaning of the word, took their flight in the dark of night around her beautiful circular vessels.

Diversity and a prevalence of art have always testified to the health and well-being of a culture. The island of Bali, as recently as the mid twentieth century, had close to 85 percent of its population involved in some form of art, be it music, painting, sculpture or dance. Anthropologists have credited its centuries of security in semi-isolation, with abundant fresh water and a developed agriculture, as the catalyst for its remarkable artistic embrace. Likewise, the Mimbre Indian culture of southwestern New Mexico inhabited a very small narrow fertile valley for almost one thousand years of peaceful existence, and produced some of the most remarkable graphic black and white designs on pottery the world has ever known.

Last weekend, on a beautifully mild Sunday in late February, Martha and I stood on a lowland rise along the western shore of the Hudson River. The snow-capped mountains of the Catskills rose majestically to our west and geese gathered in the calm estuaries at the water’s edge. We were there in this quiet, semi-remote reach of land between mountain and river at the request of a friend, to offer suggestions towards the design and construction of a remarkable organic structure to be built on the site during this coming year. A sound temple, with walls of woven white oak, will rise like a sacred flower along the river. An architectural vessel of acoustic vision, honoring the art of handwork. A form for the future by a group of young artists who have arrived at the helm of this boat just as their time takes to a new light. This, like all art, is hard to contain or describe with words beyond its own remarkable skin. A pulsating heart that gives life to form and brings color to blood gives flight to all of us.

otego, new york

february 2013

Photos by the author