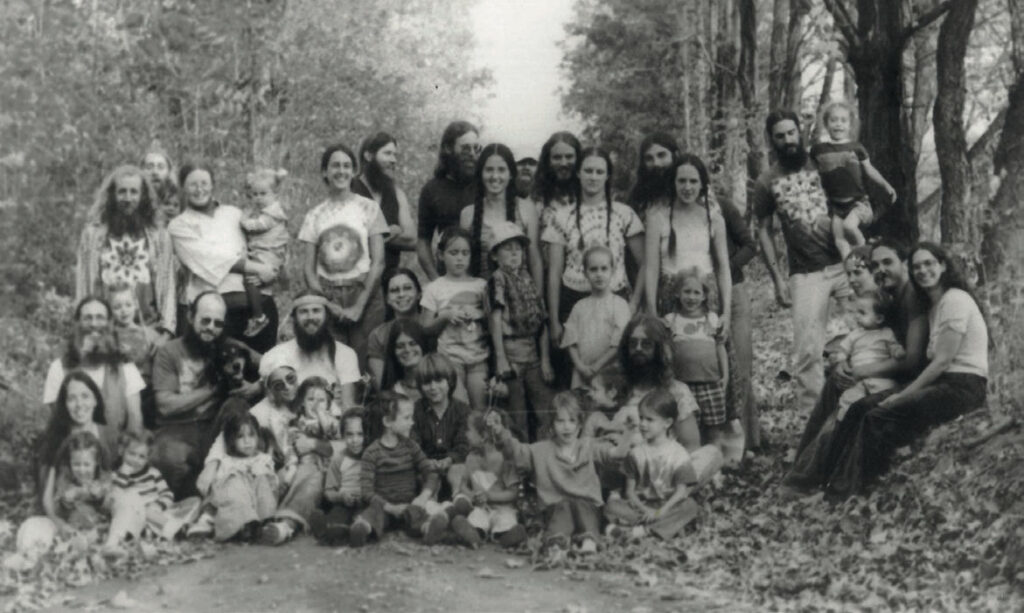

Venture over the back of Leland Hull Road today and take the righthand fork. You won’t find much. But forty years ago, this wooded hillside was alive with Franklin’s fabled utopian community, The Farm.

The ideal of communal living had its first American flush during the 19th century, with nearly eighty communities starting up in the 1840s alone. But none of these – such as New Harmony in Indiana (1825 – 1829) or the Oneida Community in New York (1848-1881) – lasted very long in fully communal form. The 1960s and 70s saw a revival of this lost ideal, as young Americans “dropped out” to find a more “righteous” way of life. But these hopeful experiments tended to be short-lived as well. A Franklin couple who lived on The Farm in the 1980s may offer insight as to why. An afternoon of friendly reminiscence with Thomas and Mary Ellen Collier over tea and brownies revealed a more three-dimensional view of The Farm than this reporter had gleaned via hints and inuendo over many years in Franklin.

You mean it wasn’t all sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll?

Not by a long shot.

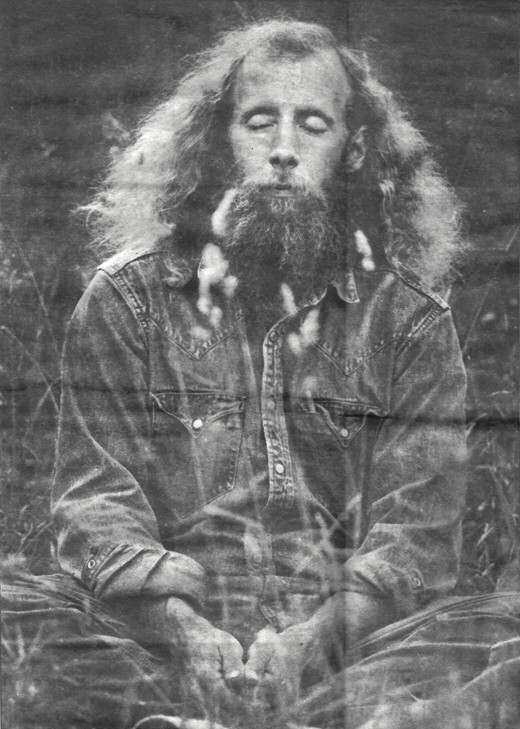

The Farm in Franklin was a “satellite” of a 1200-acre spiritual community established in 1971 by hippie-activist Stephen Gaskin and a group of like-minded friends. They set out from San Francisco in a sixty-vehicle caravan – painted school buses and all – landing in Summertown, TN. The community was non-denominational, open to all, and strictly vegan.

Mary Ellen: “Our main protein was beans…First thing we learned was that a vegan lifestyle would provide enough resources for all the world to eat – an equitable diet.”

Membership required signing a vow of poverty.

Mary Ellen: “It wasn’t hard for me. I didn’t own anything. We had a funny rule of thumb: anything bigger than a guitar, it belonged to the Farm…You could have your own personal possessions, but…if you came with a car, it went to the motor pool…If somebody passed and you got an inheritance, you were expected to give it to The Farm.”

Thomas: “That was the glue that held the whole thing together.”

Regular Sunday services were an hour-long meditation, ending with a collective Om, after which Stephen Gaskin would preach.

Was he very charismatic?

Mary Ellen: “In a low-key way. The kind of guy who just got up and started talking. He was just smart, so smart.”

Thomas Collier nods. “He just spoke truth.”

Mary Ellen’s connection with The Farm began with finding Ina May Gaskin’s book, Spiritual Midwifery, in her local library.

“I was pregnant with my boyfriend’s kid, but he’d turned abusive, someone it wouldn’t be good to raise a child with, so I moved back to my parents’ house in Long Island. I was seven months pregnant, but I didn’t want a hospital birth…I wanted more control over it.”

Spiritual midwifery was central to The Farm in Tennessee and seemed to offer a solution: “Hey, ladies! Don’t have an abortion, come to The Farm and we’ll deliver your baby and take care of it, and if you ever decide you want it back, you can have it.”

Mary Ellen wrote to Ina May and was invited to come. She had her daughter Tessa there, then became a member and stayed for three years. Thomas came to The Farm around the same time, but with over a thousand residents, they didn’t meet till later.

The Farm had a charitable branch called Plenty (still active today as Plenty International), formed to help after a devastating earthquake in Guatemala. In 1978, Plenty moved a group of Farm folks into an abandoned apartment building on East 167th Street in the South Bronx, then a famously rough neighborhood and critically underserved by the city. As squatters, they renovated the building, “and the city was glad to see it.” Plenty ran EMT training courses there and operated an ambulance service in an area where there had been none. Mary Ellen moved to the South Bronx in January of 1979 and there she met Thomas.

Thomas learned of The Farm from a friend who’d followed Stephen Gaskin’s caravan. He was from Jacksonville, Florida and ready for an alternative lifestyle. The community’s main source of income came from construction work, and Thomas arrived with those very skills. “I had all my hand tools with me… Immediately went to work on the carpentry crew, building the school…I was young and single and strong and needed. Same thing up here: I came up here and they wouldn’t let me leave.”

He laughs. “One of the first days, I had my pouch on, my hammer and stuff. Kid walks up, he says, ‘What’s that made of?’ ‘Well…leather.’ ‘Man, we don’t wear leather on The Farm!’ And I’m like: Busted! But I didn’t know! Next day, I just had a cloth apron.”

Primo Construction, a familiar name in Franklin, sponsored and renovated the South Bronx center. Thomas also recalled a job replacing windows in skyscrapers.

“Eighteen windows in the back of a station wagon! And ‘cuz it was a car, you couldn’t park it anywhere!”

Later, among many other projects, Primo built some of the barns at the Walton fairgrounds.

Thomas and Mary Ellen went back to Tennessee in 1980, got married, had a second daughter, then moved to Franklin in January of 1981.

The Farm’s Franklin “satellite” was a 340-acre former sheep farm “way up the end of the hollow, pretty isolated,” bought in 1975 from John Campbell, Sr., by Syracuse University students wanting to follow a collective living model. They had visited The Farm in Tennessee, but it wasn’t taking new members.

In a 2014 The Daily Star article, local historian Mark Simonson quoted the group’s 25-year-old spokesman, Martin Goldberg: “We believe in God and that all people are the same…We don’t use drugs, or stimulants, we don’t even drink coffee…We’re into getting married, working hard…you won’t find any orgies or wife-swapping here. We’re so straight, it’s ridiculous.”

So much for sex and drugs.

Part of the Franklin farm’s mission was to provide emotional support for the South Bronx group. “So people could get out of the city and come up here for weekends.”

Mary Ellen recalls, “But it was really cold. There was a lot of snow!”

Thomas chimes in: “Lots of firewood! That winter went down to 25 below!”

The housing included two trailers, a small existing farm building, a large old barn, and a three-story house built after the purchase. Multiple families lived in each building.

Mary Ellen: “When we first got there, we were living with another couple. We each had a bedroom, all our kids shared a kid room…The trailers weren’t very well insulated…but the Big House was nicely built. It’s still standing up there.”

Eventually, there were fifteen to twenty families, spread out. Each dwelling had its own kitchen, but the big house had a communal kitchen and a soy dairy for making tofu. In keeping with the vegan lifestyle, no animals were kept, “apart from a couple of dogs and whatever cats showed up. We had a horse and a pony for a while, too.”

Thomas: “That kind of follows the Buddhist precepts of, y’know, do no harm.”

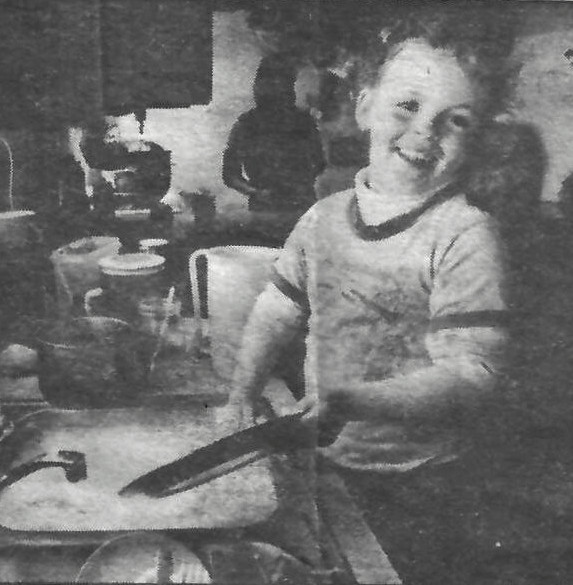

Mary Ellen: “We bought beans in bulk…we made all our own bread…and grew as many vegetables as we could. The Farms were supported by people working off the Farm, so Thomas and most of the men operated Primo Construction…the women and children stayed on the farm, gardening, housekeeping, kid care, and homeschooling the kids…I was very comfortable living in groups. I loved having women friends all around.”

Thomas says, “My highpoint was getting married, that wedding we shared with two other couples. The wedding cakes consisted of eleven sheet cakes!”

In 1983, the property was sold to the mega-developer Patten Realty, to be divided into 42 five-acre lots.

The Franklin Farm disbanded.

(To be continued…)

Part II, in the NFR’s summer issue, will detail the causes of the Franklin Farm’s demise.